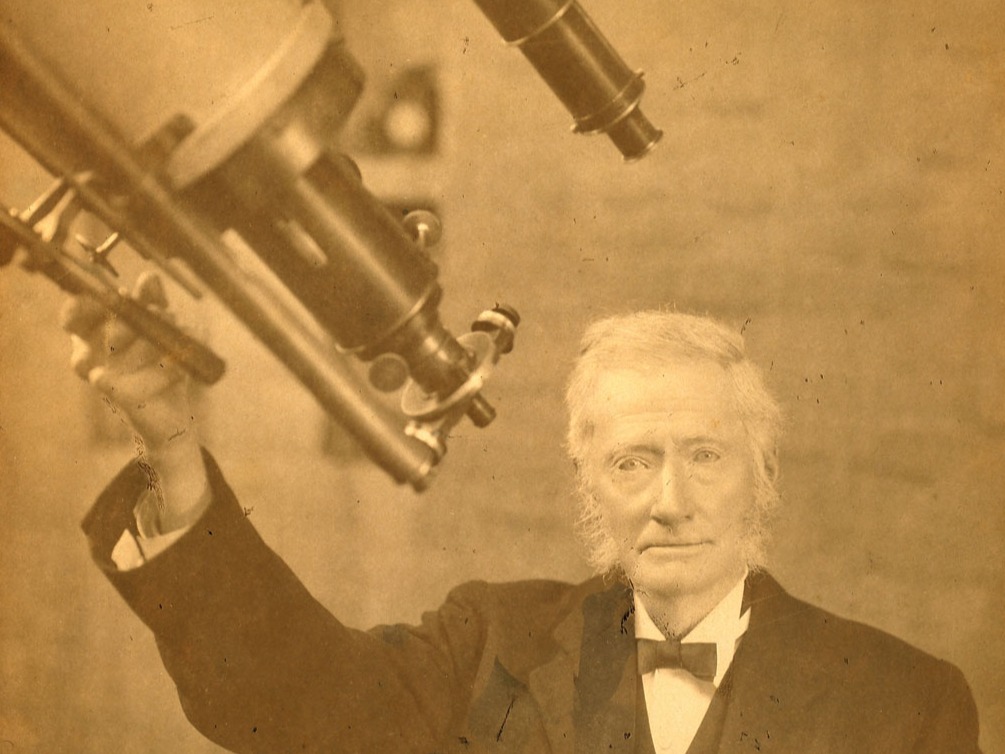

Starry Night is an online exhibition about the life and achievements of the renowned 19th century astronomer, John Tebbutt. After discovering the Great Comet of 1861 at the age of 26, he quickly achieved international recognition and was soon widely considered the foremost astronomer in Australia. He carried out an impressive range of astronomical observations and authored almost 400 publications, all from his observatories located in Windsor, NSW.

Although astronomy was his driving passion, he was also involved in several societies, ran a local time service, studied local weather and flooding, and wrote about religion. As a man he was forthright and factual, and held himself and others to high standards.

Featuring interviews, a virtual tour of his surviving observatories, archival material and photographs of Tebbutt’s original instruments, this exhibition delves into the world of this fascinating figure.

Early Life and Background

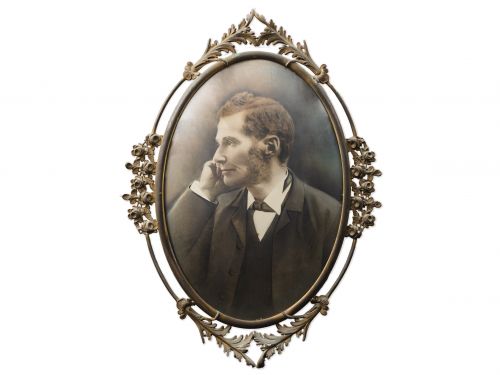

John Tebbutt was born in Windsor, New South Wales on the 25th of May 1834. He was the eldest child of John Tebbutt Senior and Virginia Saunders. His only sibling, a younger sister named Ann, died in infancy.

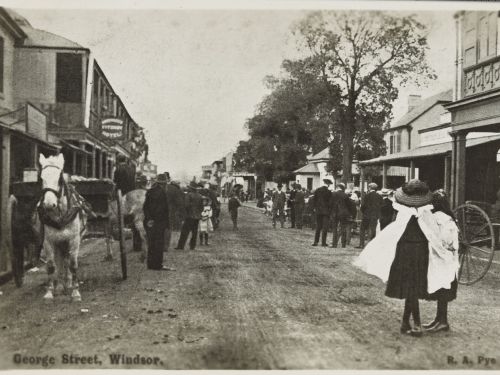

The Tebbutt family came to Australia from England as free settlers on the ship the Nile. Tebbutt’s grandfather (also John), his wife Ann and their three children, John (Tebbutt’s father), Thomas and Elizabeth, all arrived in Sydney in late 1801. The land promised to the Tebbutts by the government upon their arrival in Australia, was found to be barren and inappropriate for farming. The family decided to refuse the land grant and soon settled in the Hawkesbury. Here, they began farming and using their earnings, eventually began a successful general store on George Street in Windsor. This business grew to become one of the main suppliers for the Hawkesbury region.

Around 1843, the Tebbutt family business closed. John Tebbutt Senior then purchased land nearby, known as the Peninsula Estate, where he pursued farming. In 1845, he built the family’s homestead at the estate. This residence still stands today.

The astronomer, John Tebbutt (Junior), married Jane Pendergast at St. Matthew’s Anglican Church in Windsor on 8 September 1857. They went on to have seven children – six daughters and one son. After his uncle died in 1865, Tebbutt received a significant inheritance. Following his father John Tebbutt Senior’s death in 1870, he also inherited the Peninsula Estate.

Education and Growing Interest in Astronomy

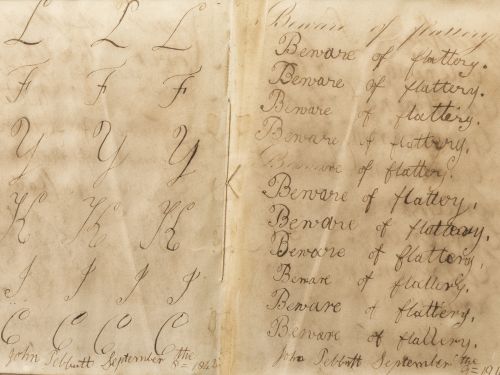

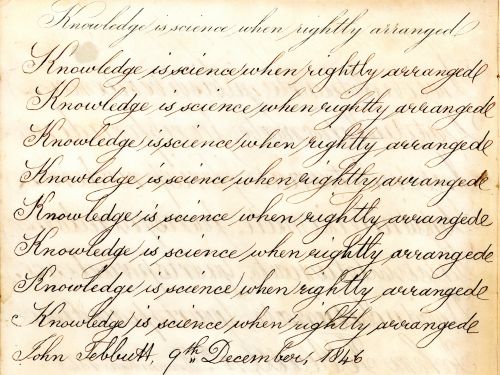

Considering the circumstances of the early colony, Tebbutt received a good education in local church schools, where he showed great promise. He was first instructed by Edward Quaife in the Church of England schoolhouse, before being transferred to what he described as an 'excellent' Presbyterian school under Reverend Matthew Adam in 1843. In 1845, Tebbutt began instruction under Reverend Henry Stiles of the Church of England, where he learned Latin, Ancient Greek, algebra, the work of Euclid and the use of the terrestrial and celestial globes. He completed his schooling at the age of 15.

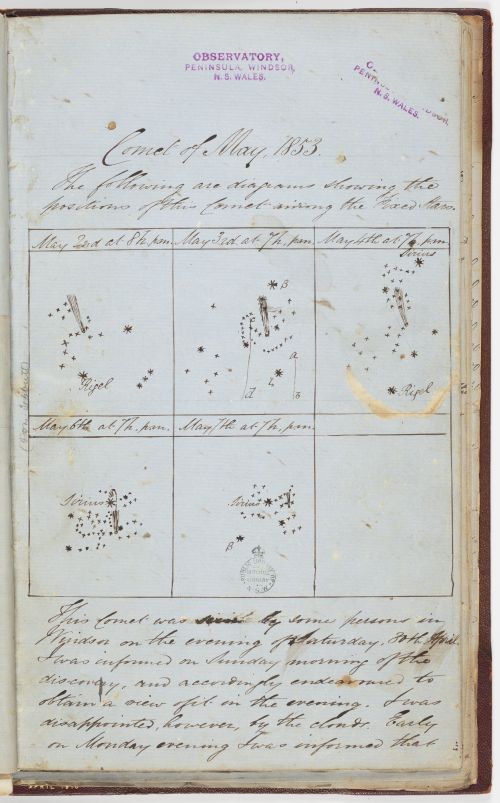

Tebbutt stated that even from a young age, he had an interest in mechanics and how things worked. He credited his schooling in the globes and his ongoing relationship with Mr Quaife, who was an amateur astronomer, as the reasons that he first became interested in astronomy – or as he termed it, ‘celestial mechanism’. This interest was strengthened after reading works by London astronomer, J.R. Hind. With a desire to undertake work in astronomy, Tebbutt soon taught himself the mathematics he would need for astronomical calculations – algebra, geometry, trigonometry and calculus. In May 1853, he made his first observations of the night sky with a small handheld telescope, studying the positions of a comet near the constellation Orion.

Personality

From his own records as well as his persistent dedication to his work, it is clear that John Tebbutt’s driving passion was astronomy. Particularly in his early journals, as he is still teaching himself the science of astronomy, his wonder at the universe and world around him is clear. He was scholarly, bright and had the endless drive to ensure he would succeed and be recognised in his chosen field. Describing his fervour in the early years of his astronomical work, Tebbutt wrote:

"I took courage and persevered in my studies, much to the disapprobation of my good father who often expressed his fears that I should ruin my health by my intense application."

– John Tebbutt, 1908

Tebbutt was extremely detail-oriented and perfectionistic, taking great pains to ensure accuracy and avoid errors in his work. Although he occasionally employed the help of assistants, he preferred to perform the more important or complex calculations himself. This perfectionism also overflowed into other areas of Tebbutt’s life – he was punctual, honest and exact. He did not appreciate ambiguity.

Although his honesty sometimes presented as bluntness in his communications with others, Tebbutt maintained correspondence with many colleagues for years and regularly responded to inquiries about astronomy. As a young man, he was involved in the Windsor Debating Society and the Windsor School of Arts. He was conservative and had no interest in public life or the happenings of society but was well-respected by his local community. No matter the time of year, Tebbutt was almost always seen about town in a black suit and white hat.

Bibliography

- Bhathal, R. (1993). Australian Astronomer John Tebbutt: The Life and World of the Man on the $100 Note. Kangaroo Press.

- In Memoriam – John Tebbutt, F.R.A.S. (15 December 1916). Windsor and Richmond Gazette, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article85881101

- John Tebbutt, Astronomer. (22 July 1899). Clarence and Richmond Examiner, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article61302653

- John Tebbutt, Astronomer. (22 October 1904). Windsor and Richmond Gazette, p. 1. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article85894177

- Mr. John Tebbutt. (26 November 1901). Clarence and Richmond Examiner, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article61290847

- Obituary. (1 December 1916). Northern Star, p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article92954976

- Orchiston, W. (1997). The Role of the Amateur in Popularising Astronomy: An Australian Case Study. Australian Journal of Astronomy, Vol. 9 (2), p. 33-66.

- Orchiston, W. (2017). John Tebbutt: Rebuilding and Strengthening the Foundations of Australian Astronomy. Springer.

- Steele, K. (1916). Early Days of Windsor N. S. Wales. Tyrrell’s Limited.

- Tebbutt, J. (1887). History and Description of Mr. Tebbutt’s Observatory, Windsor, New South Wales. Printed for the author by Joseph Cook & Co, Printers.

- Tebbutt, J. (1908). Astronomical Memoirs. Printed for the author by Frederick W White, General Printer.

- Vale! John Tebbutt. (15 December 1916). Windsor and Richmond Gazette, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article85881098

19TH CENTURY AUSTRALIAN ASTRONOMY

By the end of the 1840s, astronomy1 in 19th century Australia was in a slump. Constructed in 1821, Parramatta Observatory closed in 1847 (in dilapidated condition), creating an absence of professional observatories in the colony. Though it had other successes, the main objective of this Observatory had been to produce a catalogue of the stars in the then under-studied southern skies. The catalogue was published in 1835 and while it was initially praised, its errors and inaccuracies soon became clear. This, combined with the perceived mismanagement of the Observatory, created an unfavourable perception of Australian astronomy.

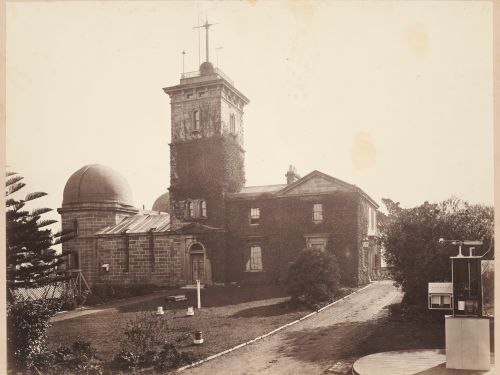

From the 1850s however, Australia’s growing population and industry necessitated the construction of state observatories that would operate local time and weather services. Williamstown Observatory was established in 1853 (replaced by Melbourne Observatory in 1863), Sydney Observatory in 1858, Adelaide Observatory in 1860,Brisbane Observatory in 1879, Hobart Observatory in 1882 and Perth Observatory in 1896. A number of notable independent observatories were also established. The astronomers of many of these observatories undertook astronomical research, and through their publications, rebuilt a standing for Australian astronomy.

Australian astronomers of the 19th century were focused on positional astronomy, determining the positions and motions of celestial objects. There were three key names during this period – Henry Chamberlain Russell, Robert Ellery and John Tebbutt. Of these, Tebbutt was the only independent astronomer. Russell and Ellery were both government astronomers.

To hear more about the context of Tebbutt’s scientific work, including 19th century Australian astronomy and the links, similarities and differences between the work of Sydney Observatory and Tebbutt's work at his Windsor Observatory, see the video below:

Notes

- Of the European tradition

Bibliography

- Bhathal, R. (1993). Australian Astronomer John Tebbutt: The Life and World of the Man on the $100 Note. Kangaroo Press.

- Jacob, A. (July 2022). Interview for John Tebbutt & Sydney Observatory. [Video]. Hawkesbury Regional Museum.

- Mauldon, M. (2013). Shaping the Domain: The Parramatta Observatory and the Study of the Southern Skies. Parramatta Park Trust.

- Orchiston, W. (2017). John Tebbutt: Rebuilding and Strengthening the Foundations of Australian Astronomy. Springer.

Entry into astronomy

In May 1853, John Tebbutt made his first astronomical observations. Using a small marine telescope, he observed a comet near the constellation Orion. He sketched the comet and determined and recorded its positions, tracking it for several weeks. Tebbutt’s records of this comet formed the beginning of a journal that he kept throughout the remainder of his career. Later, in 1858, and with greater experience under his belt, Tebbutt also calculated a rough orbit for the comet using his 1853 observations.

In his memoirs, Tebbutt describes the other key astronomical events which encouraged him to continue pursuing the science in the early years. In 1854, he followed sunspots to verify the Sun’s rotational period, which he had read about in popular astronomy works. In 1857, a total eclipse of the Sun whips up palpable excitement that ‘astonishes’ his father. Tebbutt tests his mathematical skills and calculates his first cometary orbits in 1858, feeling pleased with the results. He is vindicated even further when a cometary orbit he calculates in 1860 has its accuracy confirmed by Government Astronomer, Reverend William Scott.

The 1861 comet

In 1861, Tebbutt made a discovery which eventually brought him international recognition in the astronomical world. On the 13th of May, Tebbutt was using his marine telescope to search for comets in the night sky when he spotted a blurry and indistinct object, barely perceptible amongst the bright surrounding stars. With great difficulty, he determined the position of the object. He checked his limited catalogues but could not find any reference to the suspicious object.

Tebbutt decided to observe the object again in the following nights but saw no change in its position. Just when he had all but given up hope that it might be a comet, on the evening of the 21st, he finally detected a change in the object’s position. He instantly sent a letter to the Government Astronomer Rev. W. Scott, relaying his findings. The following night it had moved again. Despite having no perceptible tail, the object was undoubtedly a comet. Tebbutt’s announcement of his discovery appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald on the 25th of May – his 27th birthday. His published letter began:

“Sir, will you kindly allow me, through the columns of your valuable paper, to apprise your astronomical readers of the presence of a comet.”

– John Tebbutt, 1861

Following the announcement, Tebbutt continued to track the comet. The next month, he published an approximate orbit for it and announced his prediction that the tail of the comet would ‘cross the Earth's path.’ Members of the public criticised his calculations and forecast but Tebbutt remained confident in his work and was supported by the Government Astronomer Scott who obtained comparable results. On the 30th of June, Tebbutt witnessed a ‘whitish light throughout the sky’; others described it as an ‘auroral glare’. These phenomena were later attributed to Earth passing through the tail of the comet, vindicating Tebbutt’s prediction.

Around this same time, the comet became visible in the northern hemisphere. It increased in brightness and became one of the most spectacular comets of the 19th century. As the recognised discoverer of this brilliant comet, Tebbutt’s place in history and astronomy was secured. The success spurred Tebbutt further in his astronomical work, inspiring him to purchase better instruments and build his first observatory in 1863.

An overview of Tebbutt’s life’s work

From his very first astronomical observations onwards, Tebbutt’s main interest and area of study was comets. He is believed to have discovered 5 comets, including another Great Comet in 1881 (which was the first comet to have its head and tail photographed successfully and the first to have its spectrum photographed). In total, Tebbutt observed at least 59 different comets, often tracking them for as many nights as possible before they faded from his view.

He reliably and devotedly determined the positions of these comets and shared his data with colleagues through his publications. Tebbutt’s contribution in this regard was extensive – between 1880 and 1899 alone, he determined 700 comet positions compared to Sydney, Adelaide and Melbourne Observatories’ combined total of 289. This data was extremely important to cometary astronomers as it could be used to determine the orbits of comets. Despite the arduous nature of the calculations involved (in the time before electronic calculators or computers), Tebbutt also computed 12 cometary orbits during his lifetime.

Tebbutt made extensive observations of variable stars, particularly contributing to our knowledge of η Carinae and R. Carinae. For instance, by combining his and others estimates of the brightness of R. Carinae, taken over many years, Tebbutt determined a period for its light fluctuations. Tebbutt is even credited with discovering a nova - Nova V728 Scorpii.

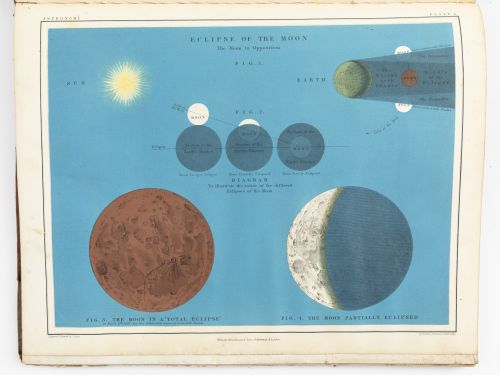

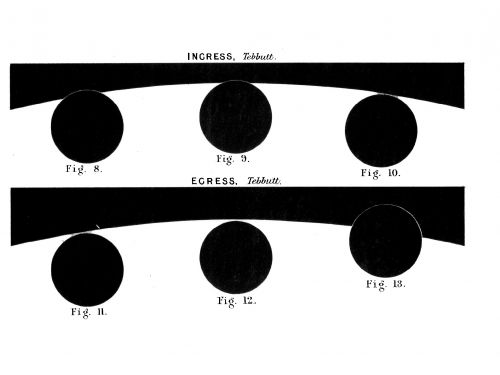

Tebbutt’s observations of double stars and minor planets provided useful data for astronomers to examine their orbits. He observed many lunar and solar eclipses, the phenomena of Jupiter’s moons, and conjunctions of planets and stars. He made substantial observations of lunar occultations of stars and used this data to determine the longitude of his Windsor Observatory with ever increasing accuracy. Tebbutt’s and other astronomers' observations of the 1874 transit of Venus (a rare event) were also used to explore the size of the solar system. In addition to all of this work, Tebbutt also observed meridian transits of stars in order to provide a local time service.

Glossary

- Astronomy: the science that studies everything in the universe beyond Earth’s atmosphere. This includes celestial objects (like stars and planets) and phenomena.

- Astronomer: a scientist who studies astronomy.

- Celestial: in or relating to the sky.

- Comets: A comet is a large object made up of frozen gases, rock and dust that orbits the Sun.

- Conjunction: when two celestial objects appear close together, from our perspective on Earth.

- Double stars: a pair of stars that, from Earth, appear close together. They may be gravitationally linked.

- Eclipse: When one celestial object (like a moon or planet) moves into the shadow of another. For example, in a lunar eclipse, Earth moves between the Sun and Moon. This stops sunlight from reaching the Moon and causes Earth’s shadow to fall on the Moon.

- Great Comet: an exceptionally bright comet that reaches naked-eye visibility and becomes known outside of the astronomical community.

- Latitude: a place’s angular distance, north or south, from the equator.

- Longitude: a place’s angular distance, east or west, from the prime meridian.

- Lunar occultations of stars: when the moon appears to move in front of a star.

- Meridian: an imaginary line passing through the north and south poles and any given point on Earth; a line of longitude.

- Meridian transit: when a celestial object moves across the observer’s meridian. Meridian transits are used for timekeeping.

- Minor planets: a celestial object that orbits the Sun but is neither a planet nor comet. Asteroids are minor planets.

- Nova: an exploding star whose brightness dramatically increases for days or weeks before returning to its former brightness.

- Observatory: a building designed for astronomical or meteorological observations.

- Orbit: the curved path that one celestial object takes around another.

- Variable star: a star whose brightness changes over a period of time.

Bibliography

- A Comet Visible. (25 May 1861). The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13059423

- Bhathal, R. (1993). Australian Astronomer John Tebbutt: The Life and World of the Man on the $100 Note. Kangaroo Press.

- Guillemin, A. (1877). The World of Comets (J. Glaishe, Trans. & Ed.). Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington. https://archive.org/details/worldofcomets00guiluoft

- Orchiston, W. (2017). John Tebbutt: Rebuilding and Strengthening the Foundations of Australian Astronomy. Springer.

- Tebbutt, J. (1883). Observations of the Transit of Venus, 1874, December 8-9, made at Windsor, New South Wales. Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society, 47, p. 89-92.

- Tebbutt, J. (1908). Astronomical Memoirs. Printed by Frederick W White, General Printer.

- Tebbutt, J. (1986). Astronomical Memoirs (reprint). Hawkesbury Shire Council.

- The Comet. (22 June 1861). Empire , p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article60495365

- The Comet’s Orbit. (15 June 1861). The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13055767

- Trouvelot, E. (1882). The Trouvelot Astronomical Drawings: Atlas. C. Scribner’s Sons.

- Weiss, E. (1888). Bilder-Atlas der Sternenwelt. J.F. Schreiber. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102144753

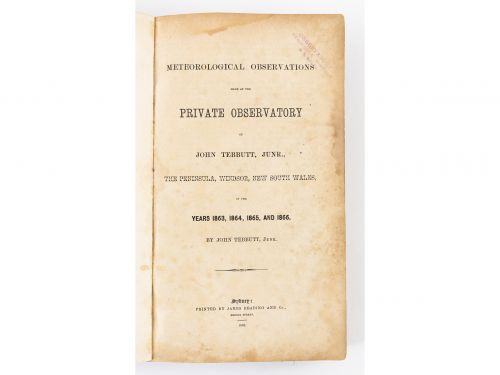

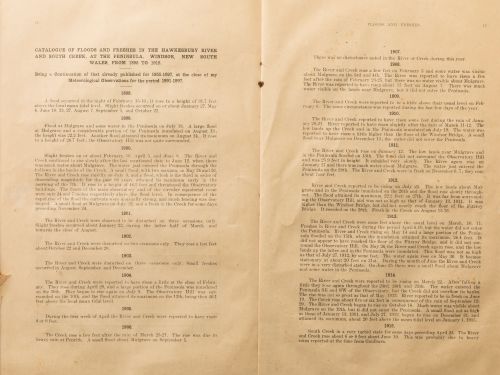

Sharing meteorological information

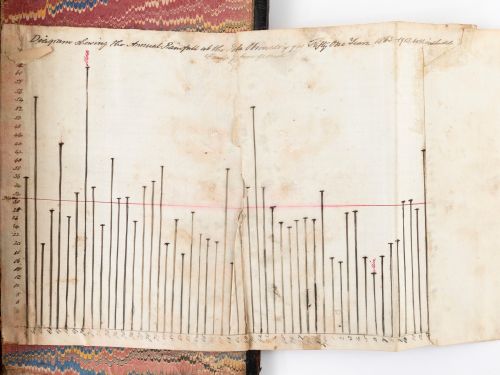

The results from Tebbutt’s daily meteorological observations, covering 1862-1915, were shared in a series of eight reports he published during his lifetime. These reports allowed readers to compare measurements (like temperature or rainfall,) day with day, month with month, or year with year. They were printed at Tebbutt’s own expense and supplied to scientific institutions worldwide.

John Tebbutt regularly shared his meteorological observations with Sydney Observatory and with Sydney and Windsor district newspapers, for the benefit of the public. He also authored papers on Australian storms, proposed the idea of a three-year cycle in local rainfall, and spent a year recording local tide levels using a gauge of his own construction.

Flood levels

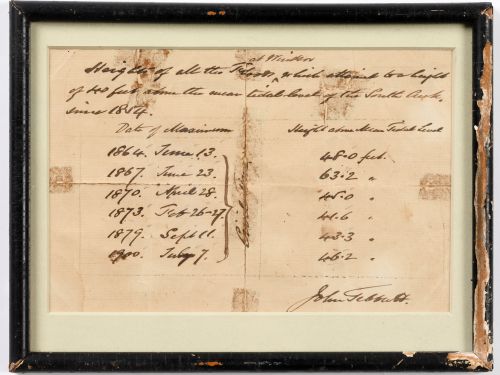

Importantly for Hawkesbury residents, Tebbutt also observed floods and freshes (minor floods) at Windsor, reliably documenting flood levels from 1855 to 1915. He also recorded some details about the progression of flood events, their impacts, and surrounding weather events. These observations were included in his published meteorological reports and were also shared in local and Sydney newspapers.

Of great interest are Tebbutt’s observations of the region’s worst ever recorded flood – the Hawkesbury’s Great Flood of 1867, when the floodwaters reached a height of more than 19 metres above normal river level. This was almost 5 metres higher than any previous flood recorded. It was also the only flood to ever enter Tebbutt’s residence or observatories. All of Tebbutt’s instruments had to be moved to higher ground for safety, as the floodwaters almost completely immersed his observatory and submerged the first floor of his residence.

Glossary

- Astronomy: the science that studies everything in the universe beyond Earth’s atmosphere. This includes celestial objects (like stars and planets) and phenomena.

- Atmosphere: the layer of air around the Earth.

- Atmospheric pressure: the weight of air above a given area on Earth’s surface.

- Climate: long-term patterns of weather.

- Evaporation: the process where a liquid turns into a gas (vapour).

- Humidity: the amount of water vapour in the air.

- Meteorology: the science that studies the weather.

- Observatory: a building designed for astronomical or meteorological observations.

- Solar radiation: energy produced by the sun.

- Temperature is a measure of hotness or coldness.

- Tides are the regular rising and falling of the water of the ocean.

Bibliography

- Astronomical And Meteorological Notes. (January 10 1881). The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28384675

- Bhathal, R. (1993). Australian Astronomer John Tebbutt: The Life and World of the Man on the $100 Note. Kangaroo Press.

- Meteorological Observations at Windsor, New South Wales. (22 October 1868). Empire, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article60828431

- Meteorological Record of the Recent Tempestuous Weather at Windsor. (29 June 1867). Sydney Mail, p. 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article166799318

- Mr. John Tebbutt. (26 February 1898). Windsor and Richmond Gazette, p. 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66437113

- Mr. John Tebbutt's Meteorological Observations. (13 June 1874). Australian Town and Country Journal, p. 18. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article70475291

- Orchiston, W. (2017). John Tebbutt: Rebuilding and Strengthening the Foundations of Australian Astronomy. Springer.

- Steele, K. (1916). Early Days of Windsor N. S. Wales. Tyrrell’s Limited.

- Tebbutt, J. (1868). Meteorological observations made at the private observatory of John Tebbutt, junr., the Peninsula, Windsor, New South Wales, in the years 1863, 1864, 1865, and 1866. Printed for the author by James Reading & Co.

- Tebbutt, J. (1871). On the Progress and Present State of Astronomical Science in New South Wales. Printed for the author by Thomas Richards, Government Printer. Also available online at http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-52761544

- Tebbutt, J. (1887). History and Description of Mr. Tebbutt’s Observatory, Windsor, New South Wales. Printed for the author by Joseph Cook & Co, Printers.

- Tebbutt, J. (1908). Astronomical Memoirs. Printed for the author by Frederick W White, General Printer.

- Tebbutt, J. (1916). Results of meteorological observations at Mr. Tebbutt's observatory, The Peninsula, Windsor, New South Wales during the period 1898-1915. Windsor & Richmond Gazette.

- The Drought. (13 September 1895). The Daily Telegraph, p. 5. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238534287

- The Meteorological Characteristics of November, 1897. (11 December 1897). Windsor and Richmond Gazette, p. 12. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article72553684

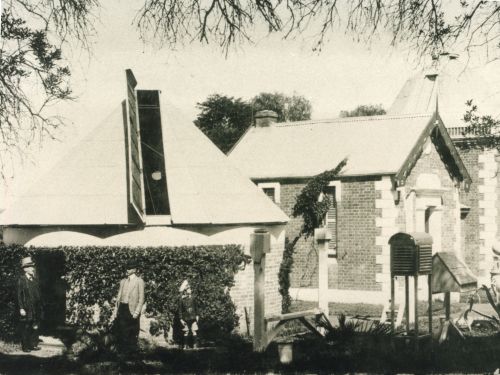

Virtual tour of Tebbutt’s observatories

Tebbutt's surviving observatory buildings, first built in 1879 and 1894, were loving restored in the 1980s. Today, they remain the private property of the Tebbutt family. Take the unique opportunity to explore these impressive and fascinating buildings in the virtual tour below.

1863 Observatory

John Tebbutt’s first observatory was built by the end of 1863, near the family residence. It was a simple building constructed of white-painted pine wood, with a slate-tile roof. There was a ‘transit’ room, a ‘prime vertical’ room, and an octagonal tower rising from the centre of the building that housed the ‘equatorial’ room. Regarding the observatory, he said:

“This was wholly the work of my own hands, and in accomplishing it I combined in my own person the handicrafts of the carpenter, the bricklayer and the slater.”

– John Tebbutt, 1908

The transit room was where Tebbutt made observations to determine local mean time and was also used as a study. There were two brick piers in the room which were used with a mount for a transit instrument, which Tebbutt purchased in 1864. Near the piers, there were slits in the roof and walls, allowing Tebbutt to make observations of the sky with the transit instrument.

The prime vertical room was located off the transit room and was built so Tebbutt could make observations to determine the latitude of his observatory. It contained a brick pier with a mount for his transit instrument and nearby slits in the roof and walls.

Finally, a set of stairs in the transit room led up to a tower containing the equatorial room. This room had a conical revolving roof with two shutters that opened to reveal the sky. A refracting telescope that Tebbutt had purchased in 1861 was mounted in this room and used to observe comets, lunar occultations of stars, and eclipses of the moons of Jupiter.

Sadly, following extensive white ant damage, the building was demolished sometime in the early 20th century.

1874 Observatory

In 1872, John Tebbutt purchased a new refracting telescope. Where his previous telescope had been 3.25 inches (8.3cm) in diameter, this one was 4.5 inches (11.4cm), allowing Tebbutt to see greater detail. Although the telescope was initially installed in the equatorial room of the 1863 observatory, the room was soon determined to be too small. This led Tebbutt to build a new observatory in 1874 that could house the new telescope. The result was a circular building constructed of pine, 3.7m in diameter. Similar to the first observatory, it also featured a revolving wooden roof, covered with canvas, and containing shutters to view the sky.

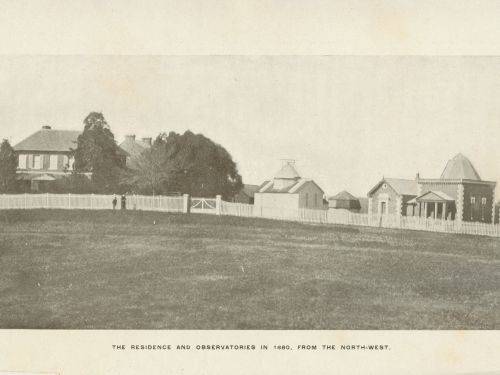

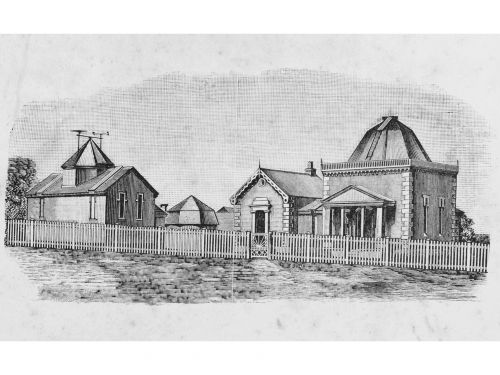

1879 Observatory

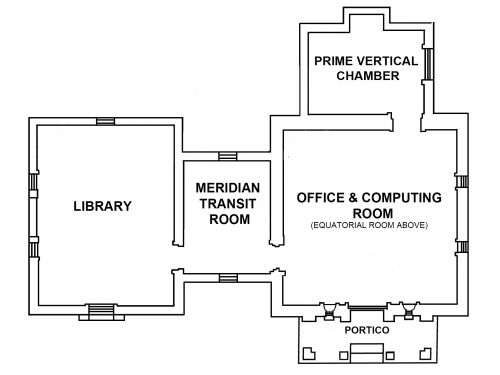

In 1879, John Tebbutt built a new, much more substantial and ornamental observatory. An example of classical Georgian architecture, it was constructed of brick and featured several rooms. The largest room functioned as an office and computing (or calculating) room. In its centre was a pyramidal pier of brick and concrete that extended up through the roof to the room above – an equatorial room. The 4.5-inch telescope was transferred to the pier in this room upon completion of the new observatory. The equatorial room was accessed via a staircase in the office and featured a revolving iron roof with an opening that extended from horizon to horizon and closed with six shutters.

As well as the office and equatorial room, there was also a prime vertical chamber (used for latitude observations) and a meridian transit room (used for time observations). Both rooms contained piers for a transit instrument and included nearby slits in the roof and walls for examining the sky. A new larger transit instrument was acquired in 1879 and was mounted on the pier in the meridian transit room.

Finally, there was a large fireproof room with heavy, iron doors that housed Tebbutt’s substantial library. It was sometimes also used as an office.

1894 Observatory

In 1886, John Tebbutt purchased a new, much larger, telescope – 8 inches (20.3cm) in diameter. This was the largest refracting telescope owned by an independent Australian astronomer during this period. The new telescope was soon installed in the 1874 observatory but was found to be an uncomfortable fit. Several years later (and after a white ant infestation), Tebbutt finally decided to replace the 1874 observatory with a larger (5.5m diameter) brick version. It was topped with a revolving iron roof, containing two long shutters. Construction of the building began in 1894 and was completed in 1895 – it was the last of Tebbutt’s observatories and still stands today.

Glossary

- Astronomy: the science that studies everything in the universe beyond Earth’s atmosphere. This includes celestial objects (like stars and planets) and phenomena.

- Astronomer: a scientist who studies astronomy.

- Celestial: in or relating to the sky.

- Comets: A comet is a large object made up of frozen gases, rock and dust that orbits the Sun.

- Eclipse: When one celestial object (like a moon or planet) moves into the shadow of another. For example, in a lunar eclipse, Earth moves between the Sun and Moon. This stops sunlight from reaching the Moon and causes Earth’s shadow to fall on the Moon.

- Equator: an imaginary line around the middle of Earth, which is an equal distance between the north and south poles.

- Equatorial room: a room containing a telescope with an equatorial mount.

- Equatorial mount: An equatorial mount for a telescope has two axes of rotation – one which is parallel to Earth’s axis, and one at right angles to it. Because Earth rotates, stars and other objects observed through a telescope appear to drift across the sky over the course of an evening. By having an axis of rotation aligned to Earth’s rotational axis, an equatorial mount makes it easier to track objects through a telescope as Earth rotates.

- Latitude: a place’s angular distance, north or south, from the equator.

- Longitude: a place’s angular distance, east or west, from the prime meridian.

- Local mean time: the mean (or average) solar time on the meridian of an observing site.

- Lunar occultations of stars: when the moon appears to move in front of a star.

- Meridian: an imaginary line passing through the north and south poles and any given point on Earth; a line of longitude.

- Meridian transit: when a celestial object moves across the observer’s meridian. Meridian transits are used for timekeeping.

- Observatory: a building designed for astronomical or meteorological observations.

- Prime vertical: an imaginary circle passing through an observer’s zenith and the east and west points of the horizon. It is perpendicular to the meridian.

- Refracting telescope: a telescope that uses a lens (instead of a mirror) to form an image.

- Transit: the act of passing through or across.

- Transit instrument: a small pivoted telescope that can only be used in one plane – the plane of the meridian. It was typically used to create star charts or determine time.

- Zenith: the point in the sky directly above a place or observer.

References

- Bhathal, R. (1993). Australian Astronomer John Tebbutt: The Life and World of the Man on the $100 Note. Kangaroo Press.

- Orchiston, W. (2017). John Tebbutt: Rebuilding and Strengthening the Foundations of Australian Astronomy. Springer.

- Tebbutt, J. (1887). History and Description of Mr. Tebbutt’s Observatory, Windsor, New South Wales. Printed by Joseph Cook & Co, Printers.

- Tebbutt, J. (1908). Astronomical Memoirs. Printed by Frederick W White, General Printer.

- Tebbutt, J. (1986). Astronomical Memoirs (reprint). Hawkesbury Shire Council.

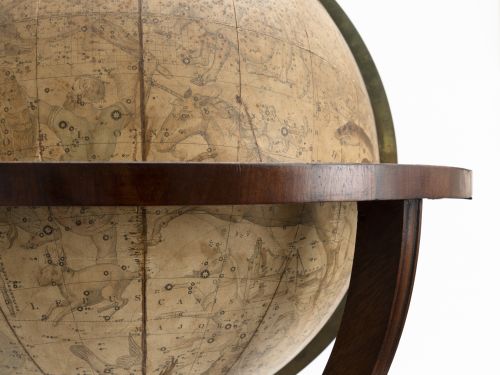

Celestial globe

1830 - 1880

manufactured by Newton, London, England

donated by the Tebbutt Family

Hawkesbury Historical Society Collection, Hawkesbury Regional Museum

Celestial globes are maps of the sky, representing the position of stars. They are based on the idea that when we look up at the sky from Earth, we effectively see it as a sphere with us at the centre. This globe belonged to John Tebbutt and could be used to estimate the time that the sun, the moon, or a star would rise or set at the horizon in his location.

Research has not yet uncovered when Tebbutt acquired the globe, but it was surely significant to him. In his memoirs and in newspaper articles, Tebbutt credited studying celestial and terrestrial globes at school as one of the reasons that he first became interested in astronomy. Photographs after 1879 also show him proudly demonstrating and posing with this beautiful celestial globe.

Watch Prof. Fred Watson, Australia’s Astronomer-at-large, discuss Tebbutt’s globe below:

8-inch refracting telescope

1882

manufactured by Grubb Telescope Company, Dublin, Ireland

Hawkesbury City Council, housed with the Tebbutt Family Collection

John Tebbutt acquired this telescope in 1886. At the time, it was the largest privately-owned telescope in Australia. Its size was a key reason Tebbutt replaced his 1874 observatory with a larger one in 1894, to better fit the instrument and allow for more comfortable observations. With the telescope, Tebbutt felt:

“…the observatory was now in a position to do work equal to that of many of the observatories of the northern hemisphere.”

– John Tebbutt, 1908

The telescope has an 8-inch aperture – significantly larger than his previous 4½-inch telescope. This meant it captured more light, allowing Tebbutt to see more detail and observe fainter objects in the sky. It also features an equatorial mount and a clock drive, allowing the instrument to automatically track a celestial object as it moves through the sky.

Utilising these features of the telescope, Tebbutt expanded his astronomical observations. For example, he continued observing his beloved comets, but could now follow them longer and see more of them than before. He could study double stars with smaller separations and could also better observe minor planets and Jupiter’s moons.

After Tebbutt’s death in 1916, the telescope was eventually sold. It passed through several amateur astronomers, travelled to the Cook Islands and New Zealand, and was sold to the Whakatane Astronomical Society in 1969. After years of bargaining between the Society and Hawkesbury City Council, it was eventually agreed that the telescope would return to Windsor. Council leased the telescope to the Tebbutt family, and it was remounted in Tebbutt’s 1894 observatory. It has been in this location since 1986.

For further information, watch Prof. Fred Watson, Australia’s Astronomer-at-large, discuss Tebbutt’s Grubb telescope below:

‘Day & Night’ marine telescope

1840s

manufactured by Lynch & Co, Dublin, Ireland

Tebbutt Family Collection

This small handheld telescope was provided to John Tebbutt by his father. He used it to make his very first astronomical observations in May 1853, studying and drawing a comet. With this small telescope and minimal other equipment, Tebbutt trained himself in the science of astronomy. This telescope was also used by Tebbutt in his discovery of the Great Comet of 1861 – the achievement that first brought him international recognition. In comparison to the 8-inch aperture of the Grubb telescope, this telescope has an aperture of 1⅝-inches.

Telescope eyepieces

19th century

various manufacturers

Tebbutt Family Collection

These eyepieces provide different levels of magnification of the image seen through a telescope. Each eyepiece has been inscribed with its level of magnification – this has allowed us to identify that four came with Tebbutt’s Grubb telescope.

Dawes solar eyepiece

1882

manufactured by Grubb Telescope Company, Dublin, Ireland

Tebbutt Family Collection

A solar eyepiece is intended to allow an astronomer to safely observe the sun. Their purpose was to prevent danger to the observer’s eye and damage to the glass of the eyepiece, by reducing the amount of light and heat travelling through them.

This example was designed for use with Tebbutt’s Grubb telescope. It features a green tinged lens and two rotating wheels – one with various aperture sizes to adjust the amount of light admitted, and one with various “London smoke” glass filters to reduce brightness. Its effectiveness is questionable, as it is uncertain whether the glass filters adequately block infrared and ultraviolet light.

Filar micrometer

1882

manufactured by Grubb Telescope Company, Dublin, Ireland

Tebbutt Family Collection

A micrometer is a specialized eyepiece, used with a telescope. It is used by an astronomer to make measurements of the separation between two celestial objects. Tebbutt used micrometers to make positional measurements of comets, planets and minor planets, and measure the separation of double stars.

Compound monocular microscope

19th century

unknown manufacturer

Tebbutt Family Collection

Microscopy was an increasingly popular pastime in the Victorian era, particularly for those interested in science.

This microscope has been passed down through the Tebbutt family. Although it is not certain that it belonged to John Tebbutt, it is known that he once owned a microscope, and the age of the instrument is appropriate.

Barometer

1862-1863

manufactured by Angelo Tornaghi, Sydney

Tebbutt Family Collection

John Tebbutt used this barometer to measure atmospheric pressure. Changes in atmospheric pressure impact the weather. Generally, a significant drop in atmospheric pressure is associated with rainy, windy or stormy weather. A significant rise in atmospheric pressure is associated with clear skies, fine weather, and light winds.

This barometer was one of a suite of instruments that Tebbutt purchased in order to also use his observatory as a meteorological station. It was made by Angelo Tornaghi, a local manufacturer who also supplied instruments to Sydney Observatory. His instruments were praised for being of similar quality to those made by respected European manufacturers.

Minimum shade thermometer

1862

manufactured by Negretti & Zambra, London, England

Tebbutt Family Collection

This thermometer was used by John Tebbutt to determine the minimum temperature of the air each day. It was placed in an area where it was protected from direct sunshine (i.e., in the shade), to avoid inaccurate readings.

Thermometer

1862

manufactured by Negretti & Zambra, London, England

Tebbutt Family Collection

John Tebbutt purchased ten different thermometers at the end of 1862 when he expanded his scientific work into meteorology. This thermometer, and the above example, were made by Negretti & Zambra, a top manufacturer of meteorological instruments. Tebbutt often purchased the best available instruments for his scientific work.

Notes

- Smaller collections of photographs and archival documents can be found at the Hawkesbury Regional Museum, Hawkesbury Library Service, Powerhouse Museum, and the Royal Astronomical Society. Some examples are seen throughout this online exhibition.

Glossary

- Astronomy: the science that studies everything in the universe beyond Earth’s atmosphere. This includes celestial objects (like stars and planets) and phenomena.

- Astronomer: a scientist who studies astronomy.

- Atmosphere: the layer of air around the Earth.

- Atmospheric pressure: the weight of air above a given area on Earth’s surface.

- Barometer: a tool used to measure atmospheric pressure.

- Celestial: in orrelating to the sky.

- Comets: A comet is a large object made up of frozen gases, rock and dust that orbits the Sun.

- Double star: two stars that appear very close to each other.

- Equator: an imaginary line around the middle of Earth, which is an equal distance between the north and south poles.

- Equatorial mount: An equatorial mount for a telescope has two axes of rotation – one which is parallel to Earth’s axis, and one at right angles to it. Because Earth rotates, stars and other objects observed through a telescope appear to drift across the sky over the course of an evening. By having an axis of rotation aligned to Earth’s rotational axis, an equatorial mount makes it easier to track objects through a telescope as Earth rotates.

- Meteorology: the science that studies the weather.

- Minor planet: an object that orbits around the sun but is not a planet, moon or comet. It includes asteroids.

- Observatory: a building designed for astronomical or meteorological observations.

- Refracting telescope: a telescope that uses a lens (instead of a mirror) to form an image.

- Temperature is a measure of hotness or coldness.

- Terrestrial: of or relating to the earth.

- Thermometer: a tool used to measure temperature.

References

- Bhathal, R. (1993). Australian Astronomer John Tebbutt: The Life and World of the Man on the $100 Note. Kangaroo Press.

- Clifton, G. (1995). Directory of British Scientific Instrument Makers, 1550-1851. Bloomsbury.

- Dawes, W.R. (1852). Description of a new Solar Eye-Piece, with some Remarks upon the Spots and other Phenomena of the Sun's Surface, as exhibited by it when applied to a Refractor of 6⅓ inches aperture. Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 21, 157-163. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1852MmRAS..21..157D/

- Denning, W.F. (1891). Telescopic Work for Starlight Evenings. Taylor & Francis.

- Jensen, L. (1992). Two Rare Solar Eyepieces. Journal of the Antique Telescope Society, Vol. 2, 3-5. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1992JATSo...2....3J/

- Lockyer, J.N. (1878). Stargazing: Past and Present. Macmillan & Co.

- Meteorological Observations at Windsor, New South Wales. (22 October 1868). Empire, p. 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article60828431

- Mollan, C. (1995). Irish National Inventory of Historic Scientific Instruments. Self-published.

- Orchiston, W. (2017). John Tebbutt: Rebuilding and Strengthening the Foundations of Australian Astronomy. Springer.

- Tebbutt, J. (1887). History and Description of Mr. Tebbutt’s Observatory, Windsor, New South Wales. Printed by Joseph Cook & Co, Printers.

- Tebbutt, J. (1908). Astronomical Memoirs. Printed by Frederick W White, General Printer.

- Watson, F. (September 2022). Interview for John Tebbutt’s Celestial Globe. [Video]. Hawkesbury Regional Museum.

- Wynter, H., & Turner, A. (1975). Scientific Instruments. Studio Vista.

Legacy

John Tebbutt left a significant legacy, befitting his life’s work. He discovered two of the most spectacular comets of the 19th century, the Great Comets of 1861 and 1881, and possibly also a nova. As early as 1860 he was offered the position of Government Astronomer of Sydney Observatory by Rev. W. Scott but turned it down, preferring to remain independent.

Tebbutt built several observatory buildings at his estate in Windsor, two of which still stand today and are listed on the NSW State Heritage Register. The work he undertook in these buildings was considered important enough for Windsor Observatory to be listed in the national ephemerides of Britain, France, Germany and the United States of America. He authored close to 400 papers and, at his own expense, published a history and description of his Windsor Observatory, annual reports of his astronomical work from 1888-1903, a series of 8 meteorological reports covering his work in this field from 1862-1915, his memoirs, and more. His extensive and reliable data was utilised by researchers worldwide.

Tebbutt helped to popularise astronomy by writing to Sydney and Hawkesbury district newspapers about his observations and upcoming astronomical events. He also used these same papers to share his meteorological and flood data with the public. For his community, where many were engaged in agricultural occupations, this information could help inform their business practices. Today, Tebbutt’s meteorological records can help us better understand the climate and flood frequency and severity at Windsor.

Considering all this, it is unsurprising that John Tebbutt was considered Australia's foremost astronomer by the end of the 19th century.

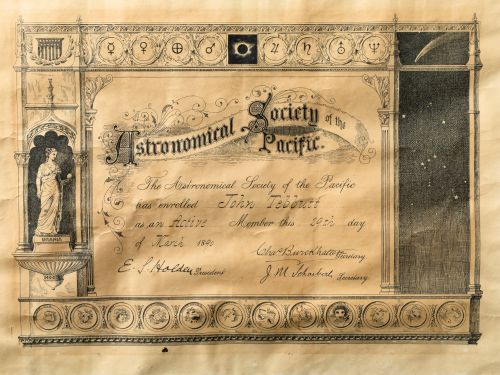

Societies

As an internationally respected astronomer, Tebbutt was a member of several learned societies. In 1861, following the Government Astronomer Rev. William Scott’s recommendation, he was elected a member of the Royal Society of New South Wales. As his reputation increased, he was eventually elected a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, London. This was a high honour for Tebbutt, and he used the acronym FRAS after his name where possible – it is even on his gravestone.

In 1882, Tebbutt formed the Australian Corps of Amateur Comet Seekers, based on similar groups in the United States of America. He wrote to about 15 different Australian astronomers but only two promised to join. The aim of the group was to divide the southern sky into zones to be monitored for comets. Each member would be assigned a different zone. Sadly, despite Tebbutt’s efforts, the society wound up within a year.

In 1895, upon the founding of the NSW Branch of the British Astronomical Society, Tebbutt was unanimously elected its first president. He was also a member of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, and a corresponding member of the Ethnographic Institute, Paris; Alliance Scientifique Universelle de Paris; Queensland Branch of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia; and the Sociedad Cientifica ‘Antonio Alzate’ of Mexico.

Although he never left Australia to visit international astronomers, this did not prevent them visiting him. In 1914, the British Association for the Advancement of Science held their meeting in Sydney. Utilising the opportunity, several of the British and local attendees travelled together to Windsor, especially to meet the renowned astronomer, John Tebbutt. These included Professor Turner, director of the Oxford University Observatory; Dr Dyson, Astronomer Royal; James Nangle, amateur astronomer and Superintendent of Technical Education for NSW; and Prof. Cooke, Government Astronomer of NSW.

Awards

Tebbutt received two medals during his lifetime. The first came early in his career, in 1867. He was awarded a Silver Medal for a paper he wrote for the Paris Universal Exhibition, titled ‘On the Progress and Present State of Astronomical Science in New South Wales’.

His second medal came after his formal retirement. In 1905, in recognition of his lifetime contribution to astronomy, the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) awarded Tebbutt the Jackson-Gwilt Medal and Gift. This award consisted of a bronze medal and £25, which Tebbutt donated to the NSW Branch of the British Astronomical Association. This prestigious prize had only been awarded twice previously. In announcing the award, the President of the RAS, Prof. Turner, stated:

“In handing this medal to the Secretary for transmission, with the gift, to Mr. Tebbutt, I will ask him to convey our hearty congratulations to the recipient on the accomplishment of half a century of single-handed astronomical work for which it would be difficult, if not impossible, to find a parallel...”

The Death of John Tebbutt

John Tebbutt died on the 29th of November 1916, aged 82. He was predeceased by his wife and three of his six daughters. His funeral is believed to have had the largest attendance of any in Windsor. Tebbutt is buried at St. Matthew's Anglican Church, in the family vault that he himself designed. Fittingly, it features a celestial sphere atop each of its four corners, fashioned in white marble.

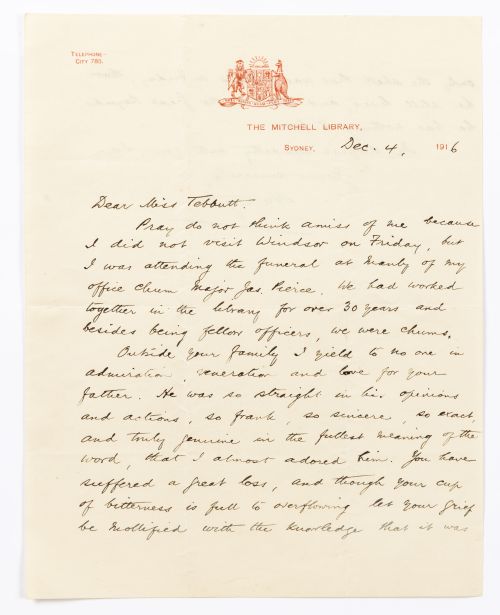

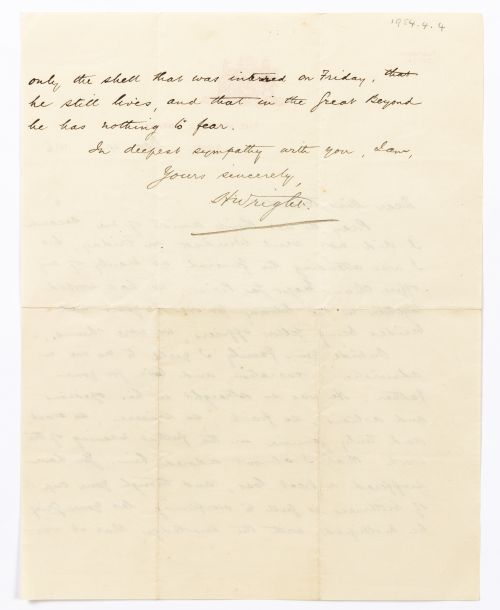

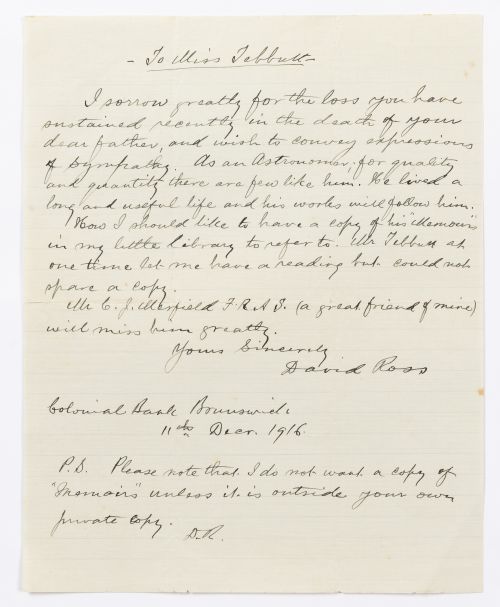

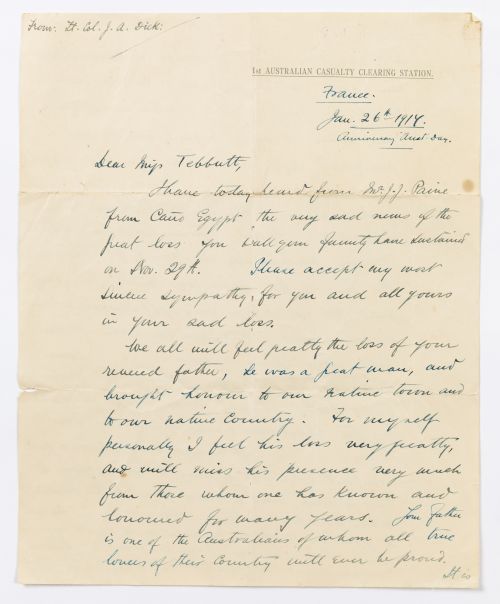

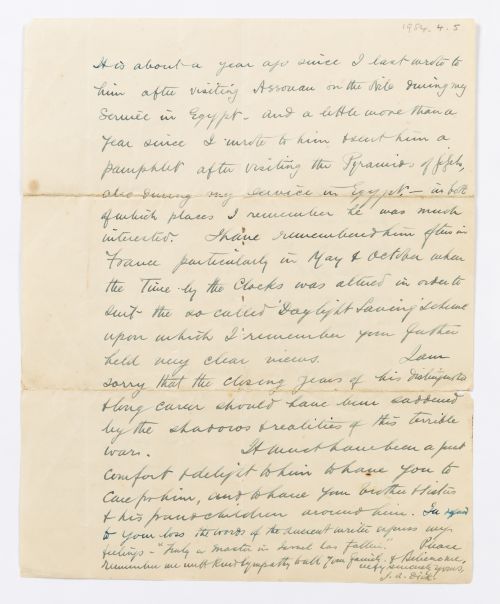

Following Tebbutt's death, the local newspapers were flooded with obituaries, In Memoriam Notices and coverage of his funeral. Letters from across the globe were also sent to the Tebbutt family, sharing their grief and sympathies. Brisbane astronomer J.P. Thomson captured the feelings of many when he wrote:

"By his death, at the ripe age of 82 years, the country is left all the poorer, and science has been robbed of one of its most brilliant jewels."

Posthumous Accolades

Years after his death, John Tebbutt's name was no longer widely recognised. In 1973 however, Tebbutt was once again in the news following the International Astronomical Union's decision to name a lunar crater after him. Ten years later, in 1984, Tebbutt and his observatories were selected to feature on the Australian $100 note. This banknote design was produced until 1996.

Today, Tebbutt's observatories remain a significant landmark in the Hawkesbury, but Tebbutt's achievements are perhaps less well-known. It is hoped that this exhibition, Starry Night: The World of John Tebbutt will draw attention to the remarkable life of this amateur scientist.

Bibliography

- Bhathal, R. (1993). Australian Astronomer John Tebbutt: The Life and World of the Man on the $100 Note. Kangaroo Press.

- Orchiston, W. (2017). John Tebbutt: Rebuilding and Strengthening the Foundations of Australian Astronomy. Springer.

- Steele, K. (1916). Early Days of Windsor N. S. Wales. Tyrrell’s Limited.

- Tebbutt, J. (1908). Astronomical Memoirs. Printed for the author by Frederick W White, General Printer.

- Vale! John Tebbutt. (15 December 1916). Windsor and Richmond Gazette, p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article85881098

Curriculum links

NSW Science and Technology Syllabus Outcomes

- Early Stage 1:

- STe-1WS-S – observes, questions and collects data to communicate ideas

- STe-6ES-S – identifies how daily and seasonal changes in the environment affect humans and other living things

- Stage 1:

- ST1-1WS-S – observes, questions and collects data to communicate and compare ideas

- ST1-2DP-T –uses materials, tools and equipment to develop solutions for a need or opportunity

- ST1-10ES-S – recognises observable changes in the sky and on the land and identifies Earth’s resources

- Stage 2:

- ST2-10ES-S – investigates regular changes caused by interactions between the Earth and the sun, and changes to the Earth’s surface

- Stage 3:

- ST3-10ES-S – explains regular events in the solar system and geological events on Earth’s surface

ACARA Science Curriculum Outcomes

- Year 1:

- AC9S1U02 – describe daily and seasonal changes in the environment and explore how these changes affect everyday life

- AC9S1H01 – describe how people use science in their daily lives, including using patterns to make scientific predictions

- AC9S1I03 – make and record observations, including informal measurements, using digital tools as appropriate

- Year 2:

- AC9S2U01 – recognise Earth is a planet in the solar system and identify patterns in the changing position of the sun, moon, planets and stars in the sky

- AC9S2I03 – make and record observations, including informal measurements, using digital tools as appropriate

- AC9S2I04 – sort and order data and information and represent patterns, including with provided tables and visuals or physical models

- Year 3:

- AC9S3H01 – examine how people use data to develop scientific explanations

- AC9S3I03 – follow procedures to make and record observations, including making formal measurements using familiar scaled instruments and using digital tools as appropriate

NSW History Syllabus Links

- Stage 1:

- HT1-2 – identifies and describes significant, people, events, places and sites in the local community over time

- HT1-3 – describes the effects of changing technology on people’s lives over time

- HT1-4 – demonstrates skills of historical inquiry and communication

- Stage 2:

- HT2-2 –describes and explains how significant individuals, groups and events contributed to changes in the local community over time

- HT2-5 – applies skills of historical inquiry and communication

- Stage 3:

- HT3-1 – describes and explains the significance of people, groups, places and events to the development of Australia

- HT3-5 applies a variety of skills of historical inquiry and communication

ACARA HASS Curriculum Outcomes:

Our resources are great for meeting the skills-based outcomes for the HASS F-6 curriculum, related to questioning and researching; interpreting, analysing and evaluating; concluding and decision-making; and communicating. They are also helpful for addressing the following knowledge and understanding based outcomes:

- Year 1:

- AC9HS1K03 – the natural, managed and constructed features of local places, and their location

- AC9HS1K04 – how places change and how they can be cared for by different groups, including First Nations Australians

- Year 2:

- AC9HS2K01 – a local individual, group, place or building and the reasons for their importance, including social, cultural or spiritual significance

- Year 3:

- AC9HS3K01 – causes and effects of changes to the local community, and how people who may be from diverse backgrounds have contributed to these changes

The Moon

Learn about moon phases and observe the night sky like an astronomer.

Comets

Learn about comets and John Tebbutt’s study of them through these fun downloadable craft activities.

The Weather

Did you know that local scientist, John Tebbutt, studied the weather? Download our activities below to learn more about the weather or make your own rain gauge.

History

Be a historian, investigate objects and photographs, and compare the past with the present!

Along with our downloadable activities, our Starry Night online exhibition is a great resource for students and educators. Use it to investigate the local history of the Hawkesbury region and study John Tebbutt – a significant individual in both local and Australian history. Our virtual tour of John Tebbutt’s observatories can even be used to take students on an online excursion!

Find-A-Words

Familiarise yourself with astronomy and weather terms, using our find-a-word activities!

Match the word to the image

Familiarise yourself with astronomy and weather terms, using our word-match activities!

Further Resources

Below, we have collated some handy resources for further learning on John Tebbutt, astronomy in NSW and Australia, and other space resources for kids.

John Tebbutt

To learn more about John Tebbutt, we recommend the following key texts, which have been referenced throughout the Starry Night online exhibition:

- Tebbutt, J. (1908). Astronomical Memoirs. Printed for the author by Frederick W White, General Printer.

- Orchiston, W. (2017). John Tebbutt: Rebuilding and Strengthening the Foundations of Australian Astronomy. Springer.

- Bhathal, R. (1993). Australian Astronomer John Tebbutt: The Life and World of the Man on the $100 Note. Kangaroo Press.

First Nations Astronomy

The First Nations Peoples of Australia – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples – maintain detailed traditional knowledge about astronomy. For thousands of years, they have observed the Sun, the Moon, and the stars to inform navigation, agricultural practices, weather predictions and more.

Astronomical objects and events have informed First Nations Peoples Law, social structures, and belief systems. They have also been the basis for stories passed down through generations.

In the video on the right, you can listen to Wiradjuri Woman and Astrophysicist, Kirsten Banks describe her passion for astronomy, the Celestial Emu, and the impact of light pollution on accessing astronomical knowledge.

More information on the astronomy of the First Nations Peoples of Australia can be found below.

Related Links

Sydney City Skywatchers

Sydney City Skywatchers aims to service amateur astronomers and astronomy enthusiasts in the city. They provide a forum for amateurs to meet and discuss astronomy, supply resources, circulate current information, and promote popular interest in astronomy.

The group was founded in 1895 as 'The New South Wales Branch of the British Astronomical Association'. John Tebbutt was the organisation's first president.

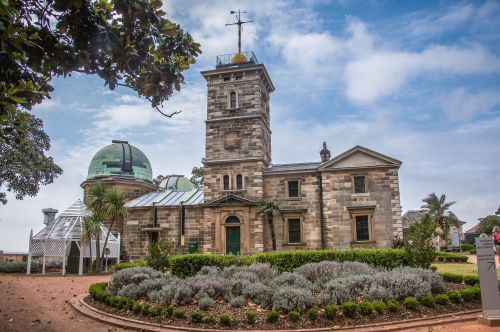

Sydney Observatory

Sydney Observatory today operates as a museum and education facility. It is located on Observatory Hill, in the inner-city Sydney suburb of Millers Point. It is a heritage-listed site and was built in 1858. It originally served as an important astronomical observatory and meteorological station, before becoming part of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in 1982.

Their website includes historical information on astronomy in Australia, as well as current guides for observing the Southern sky.

Australian Space Discovery Centre

The Australian Space Discovery Centre, located in Adelaide, is a great place to learn about Australia’s role and achievements in the space sector. Their website includes learning resources for kids and briefly details Australian space milestones after 1957.

Australian Space Discovery Centre | Department of Industry, Science and Resources

NASA for Kids

NASA’s award-winning Space Place website engages primary aged children in space and Earth science through interactive games and hands-on activities.

This project is supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW

We thank the Tebbutt family and our interviewees for their involvement. Contemporary photos of Tebbutt's objects and observatories, unless otherwise indicated, is by Silversalt Photography. Videography by Simon Cadman. Virtual tour by Simply360.

We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the Hawkesbury, the Dharug and Darkinjung peoples, and their continuing connections to land, sea, culture and community. We pay our respects to their Elders past and present. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be aware that this website may contain images or names of deceased persons.

Page ID: 232314